The Time Machine

The Time Machine

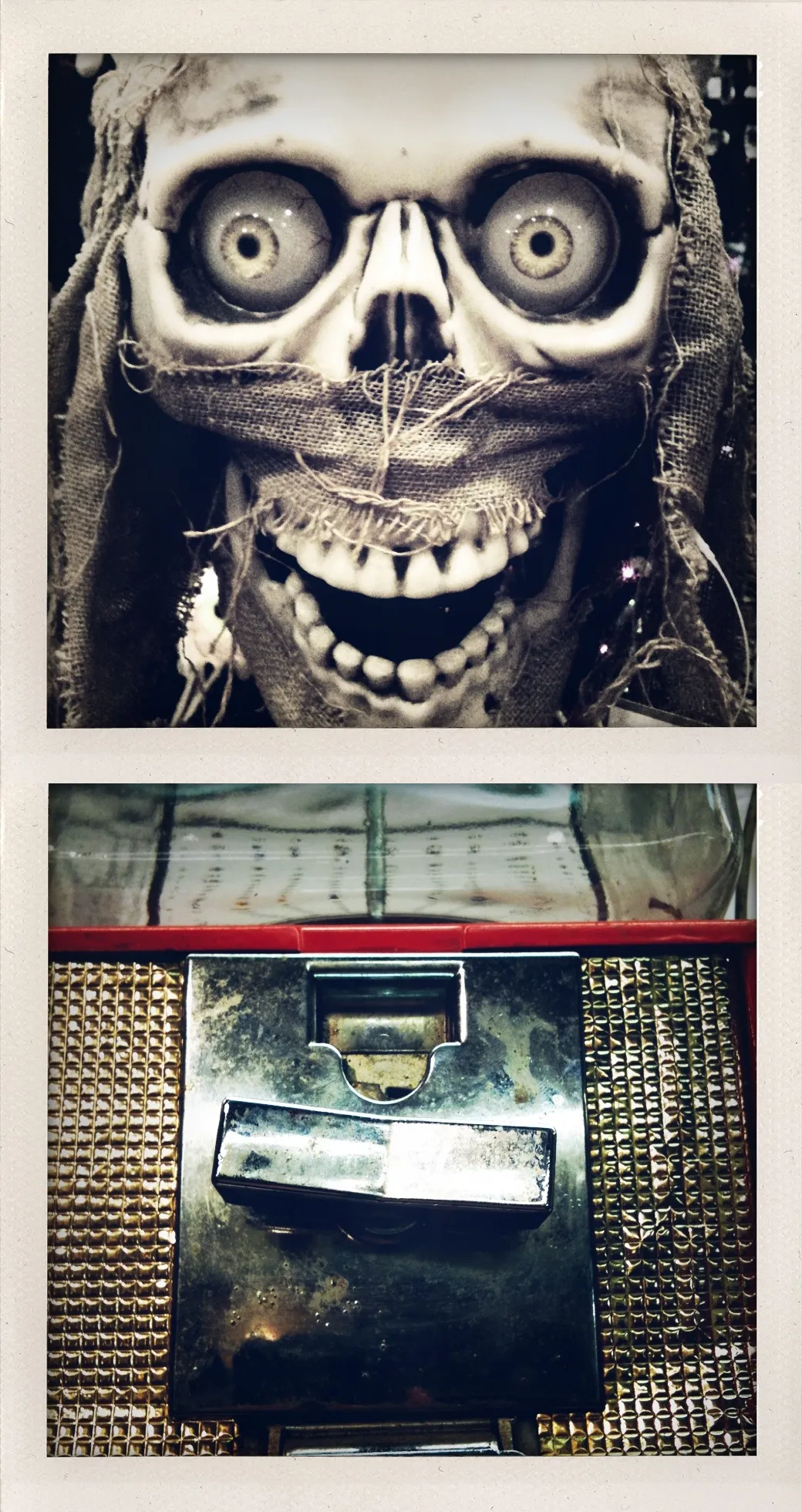

This diptych pairs a vintage gumball machine with a burlap-wrapped skull, offering a darkly literal take on time travel. The chrome mechanism below functions as the “time machine”—insert coin, turn handle, await transport. But this machine delivers on its promise with brutal honesty: travel forward in time, and your body experiences every year of the journey.

The skull above represents the successful traveler, arrived at the future but biologically aged to death en route. The gumball machine’s element of chance deepens the joke—you never know what you’ll get, but the outcome is always decay. The greenish cast unifying both frames suggests the toxic consequence of the transaction.

The work subverts science fiction’s fantasy of temporal tourism while critiquing nostalgia’s false promise: you can access another time, but the cost is always paid in the present.

Essay written: November 2025

This diptych pairs a vintage gumball machine with a burlap-wrapped skull, offering a darkly literal take on time travel. The chrome mechanism below functions as the “time machine”—insert coin, turn handle, await transport. But this machine delivers on its promise with brutal honesty: travel forward in time, and your body experiences every year of the journey.

The skull above represents the successful traveler, arrived at the future but biologically aged to death en route. The gumball machine’s element of chance deepens the joke—you never know what you’ll get, but the outcome is always decay. The greenish cast unifying both frames suggests the toxic consequence of the transaction.

The work subverts science fiction’s fantasy of temporal tourism while critiquing nostalgia’s false promise: you can access another time, but the cost is always paid in the present.

Essay written: November 2025