The Industrial Revolution

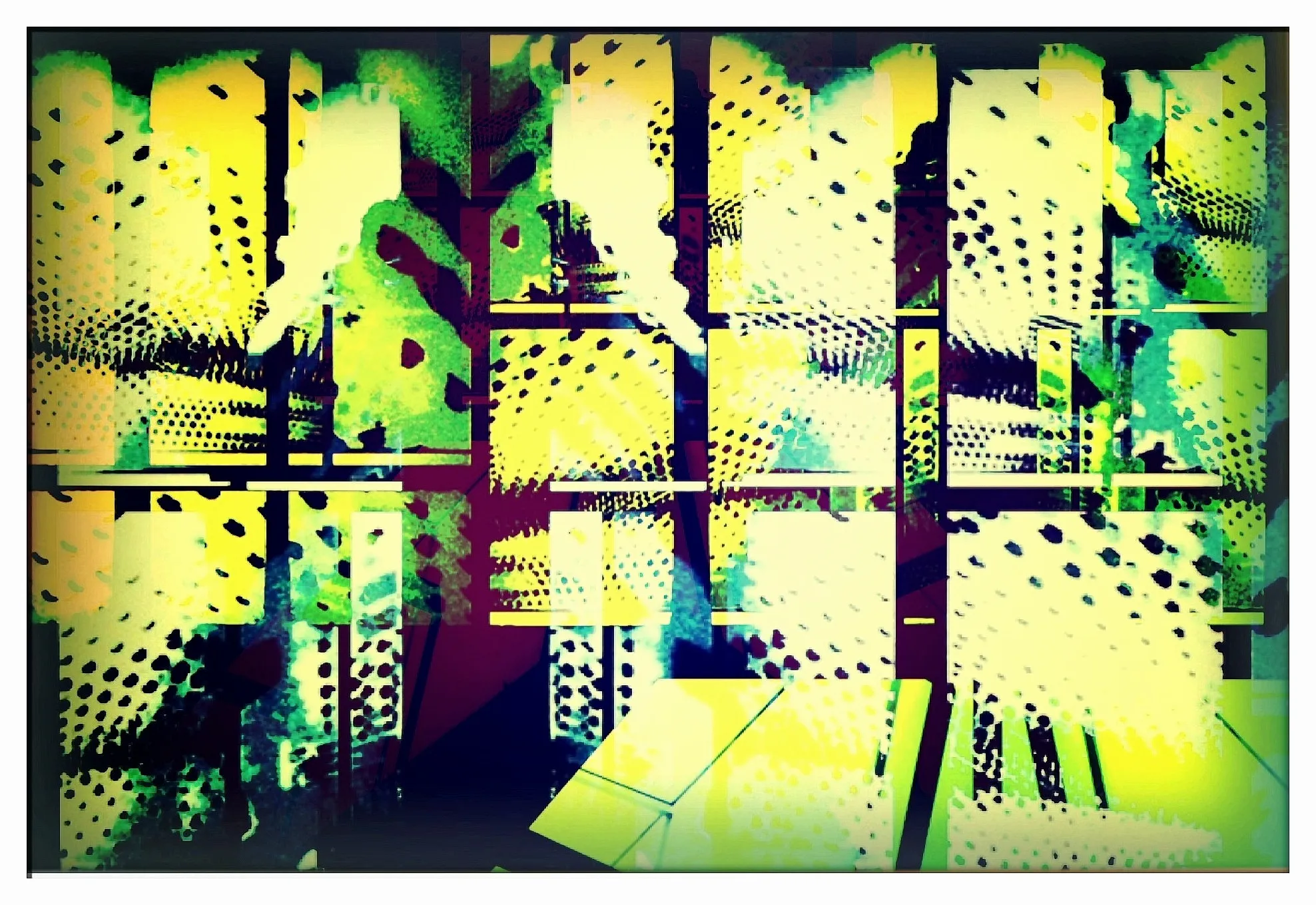

iPhone-generated halftone patterns, fractured grids, and toxic color palettes examine industrialization’s ongoing effects. The halftone screen—a mechanical printing relic—becomes a symbol of standardization and atomization, its deliberate misregistrations exposing how systems break and dehumanize.

Electric greens, jaundiced yellows, and bruised violets evoke both industrial signage and contemporary screen glow, linking 19th-century mechanization to modern algorithmic systems. Both operate through similar logic: repetitive, scalable, opaque. Human figures flicker as spectral presences before dissolving—the laboring body erased within productivity systems. The work draws direct lines from steam and steel to algorithms and automation, presenting industrial aesthetics not as historical artifact but as active machinery grinding beneath our image-saturated present.

Essay written: November 2025