Blight in Yellow Waters

Blight in Yellow Waters

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

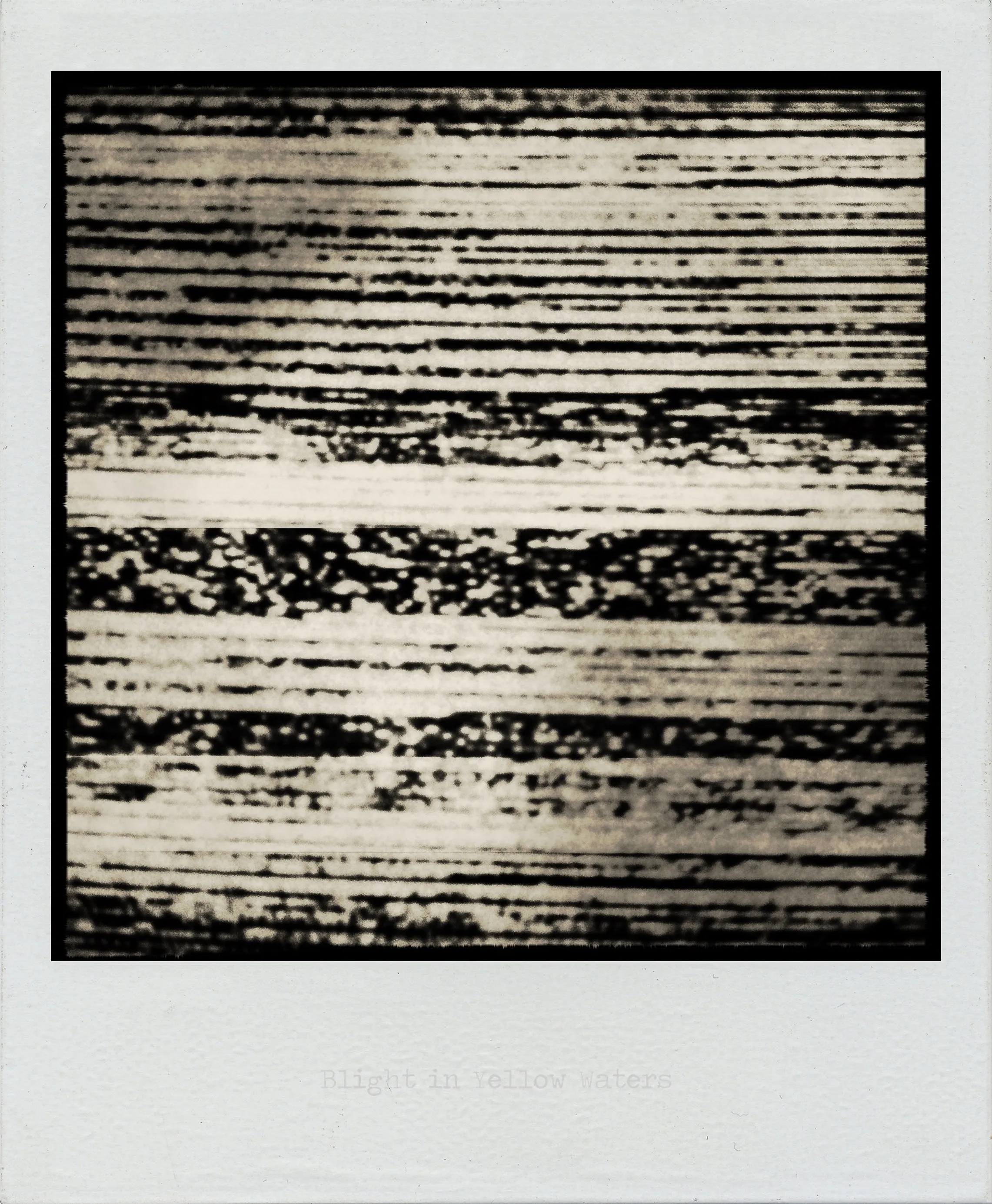

I’m looking at horizontal striations - bands of light and dark that read like layers of accumulated decay. The lighter areas appear weathered, almost bone-like in their pallor, while the darker bands suggest rot, disease, or severe deterioration eating through whatever material this is.

The texture feels organic - this could be wood that’s been submerged and is now showing the effects of water damage and biological decay. The “blight” manifests as these darker intrusions spreading through the horizontal grain, breaking down structure, corrupting what was once whole. There’s a rhythm to it - the alternating pattern suggests time, cycles, the slow work of deterioration. The “yellow waters” of the title might speak to stagnation, pollution, or the discoloration that comes with neglect and decay.

What strikes me is how the photograph abstracts this decay into something almost beautiful - a formal study of texture and contrast, even as it documents deterioration. The documentary and the aesthetic exist simultaneously. It’s both evidence of decline and a consideration of what patterns emerge when things break down.

The framing is tight, forensic. You’re asking us to look closely at the texture of decay itself.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

Blight in Yellow Waters presents a visual field dominated by horizontal bands of interference. The image’s structure recalls analog broadcast static, with irregular densities and granular distortions interrupting what might otherwise be read as patterned repetition. This isn’t a glitch captured in passing—it’s a studied engagement with the aesthetics of malfunction, using the digital medium to evoke the analog’s collapse.

The image is strictly monochrome—black, white, and the intervening grays. This limited tonal range sharpens the viewer’s attention to texture and rhythm. The title, however, introduces an incongruity: yellow and waters are absent both chromatically and iconographically. The disjunction seems intentional. If taken literally, the title references ecological damage—possibly chemical pollution or eutrophication. But without visual referents, the viewer is left to reconcile the conceptual framing with an image that actively resists narrative or representation.

This resistance is significant. While contemporary visual culture often privileges high-resolution clarity and overdetermined meaning, this image withholds both. It functions within a lineage of works that turn technological decay into aesthetic strategy—think Nam June Paik’s magnetized TVs or more recent glitch aesthetics where corrupted files become material. But where those works sometimes foreground the machine’s failure, this image situates failure as the baseline condition. There’s no visible interruption—only the ongoing presence of interference as image.

The danger here is that the work might be misread as purely formalist. Without a contextual anchor, its surface qualities—texture, pattern, contrast—could be reduced to design elements. But the title frustrates that interpretation. It insists on metaphor, even allegory, without supplying any illustrative content. The result is a conceptual dissonance: an abstract visual field paired with a title saturated in implication.

One way to approach this tension is ecocritically. The static could be seen as a visual analogue to environmental blight—not its image, but its effect. Just as industrial runoff renders water toxic and opaque, here the image is occluded, overwritten by noise. The viewer can’t “see through” to any underlying scene. There is no landscape, no figure—just interference. This may be a visual metaphor for obfuscation, not just environmental but epistemological. What does it mean to perceive through layers of distortion? What systems produce that distortion, and who benefits from it?

There’s also a media-historical reading to consider. The horizontal scan lines echo CRT-era displays, now obsolete. The image might then reference a discarded technology—an afterimage of an analog age drowned in digital flow. The “blight” could just as easily describe the transition from one mode of seeing to another, and the cultural erasures that come with it. In that sense, Blight in Yellow Waters participates in a broader critique of mediated vision. It’s not just about what’s lost in translation, but about the act of translation itself.

The image also raises a compositional question: what anchors this work as a photograph? There’s no discernible subject, no referential index. If this is a photo, what is it of? If it’s a screen capture, is it documenting or fabricating? These questions point to the instability of photographic truth, a foundational concern in the post-digital era. The medium’s claim to representation is undercut by its own abstraction.

Ultimately, Blight in Yellow Waters functions as a provocation more than a resolution. It doesn’t illustrate pollution, but instead enacts its visual logic. It withholds clarity not to frustrate but to ask how vision operates under conditions of systemic interference. The result is a kind of anti-image—neither fully representational nor fully abstract, situated in the blurred zone between documentary and denial.

This makes the work difficult to consume quickly, but that may be its strength. It compels a slower, more critical engagement—one that begins with visual noise but ends in conceptual signal. In a time when both ecology and information systems are increasingly opaque, Blight in Yellow Waters offers no easy answers, only the urgent necessity of looking harder.

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

I’m looking at horizontal striations - bands of light and dark that read like layers of accumulated decay. The lighter areas appear weathered, almost bone-like in their pallor, while the darker bands suggest rot, disease, or severe deterioration eating through whatever material this is.

The texture feels organic - this could be wood that’s been submerged and is now showing the effects of water damage and biological decay. The “blight” manifests as these darker intrusions spreading through the horizontal grain, breaking down structure, corrupting what was once whole. There’s a rhythm to it - the alternating pattern suggests time, cycles, the slow work of deterioration. The “yellow waters” of the title might speak to stagnation, pollution, or the discoloration that comes with neglect and decay.

What strikes me is how the photograph abstracts this decay into something almost beautiful - a formal study of texture and contrast, even as it documents deterioration. The documentary and the aesthetic exist simultaneously. It’s both evidence of decline and a consideration of what patterns emerge when things break down.

The framing is tight, forensic. You’re asking us to look closely at the texture of decay itself.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

Blight in Yellow Waters presents a visual field dominated by horizontal bands of interference. The image’s structure recalls analog broadcast static, with irregular densities and granular distortions interrupting what might otherwise be read as patterned repetition. This isn’t a glitch captured in passing—it’s a studied engagement with the aesthetics of malfunction, using the digital medium to evoke the analog’s collapse.

The image is strictly monochrome—black, white, and the intervening grays. This limited tonal range sharpens the viewer’s attention to texture and rhythm. The title, however, introduces an incongruity: yellow and waters are absent both chromatically and iconographically. The disjunction seems intentional. If taken literally, the title references ecological damage—possibly chemical pollution or eutrophication. But without visual referents, the viewer is left to reconcile the conceptual framing with an image that actively resists narrative or representation.

This resistance is significant. While contemporary visual culture often privileges high-resolution clarity and overdetermined meaning, this image withholds both. It functions within a lineage of works that turn technological decay into aesthetic strategy—think Nam June Paik’s magnetized TVs or more recent glitch aesthetics where corrupted files become material. But where those works sometimes foreground the machine’s failure, this image situates failure as the baseline condition. There’s no visible interruption—only the ongoing presence of interference as image.

The danger here is that the work might be misread as purely formalist. Without a contextual anchor, its surface qualities—texture, pattern, contrast—could be reduced to design elements. But the title frustrates that interpretation. It insists on metaphor, even allegory, without supplying any illustrative content. The result is a conceptual dissonance: an abstract visual field paired with a title saturated in implication.

One way to approach this tension is ecocritically. The static could be seen as a visual analogue to environmental blight—not its image, but its effect. Just as industrial runoff renders water toxic and opaque, here the image is occluded, overwritten by noise. The viewer can’t “see through” to any underlying scene. There is no landscape, no figure—just interference. This may be a visual metaphor for obfuscation, not just environmental but epistemological. What does it mean to perceive through layers of distortion? What systems produce that distortion, and who benefits from it?

There’s also a media-historical reading to consider. The horizontal scan lines echo CRT-era displays, now obsolete. The image might then reference a discarded technology—an afterimage of an analog age drowned in digital flow. The “blight” could just as easily describe the transition from one mode of seeing to another, and the cultural erasures that come with it. In that sense, Blight in Yellow Waters participates in a broader critique of mediated vision. It’s not just about what’s lost in translation, but about the act of translation itself.

The image also raises a compositional question: what anchors this work as a photograph? There’s no discernible subject, no referential index. If this is a photo, what is it of? If it’s a screen capture, is it documenting or fabricating? These questions point to the instability of photographic truth, a foundational concern in the post-digital era. The medium’s claim to representation is undercut by its own abstraction.

Ultimately, Blight in Yellow Waters functions as a provocation more than a resolution. It doesn’t illustrate pollution, but instead enacts its visual logic. It withholds clarity not to frustrate but to ask how vision operates under conditions of systemic interference. The result is a kind of anti-image—neither fully representational nor fully abstract, situated in the blurred zone between documentary and denial.

This makes the work difficult to consume quickly, but that may be its strength. It compels a slower, more critical engagement—one that begins with visual noise but ends in conceptual signal. In a time when both ecology and information systems are increasingly opaque, Blight in Yellow Waters offers no easy answers, only the urgent necessity of looking harder.