Man in the Shards

Man in the Shards

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

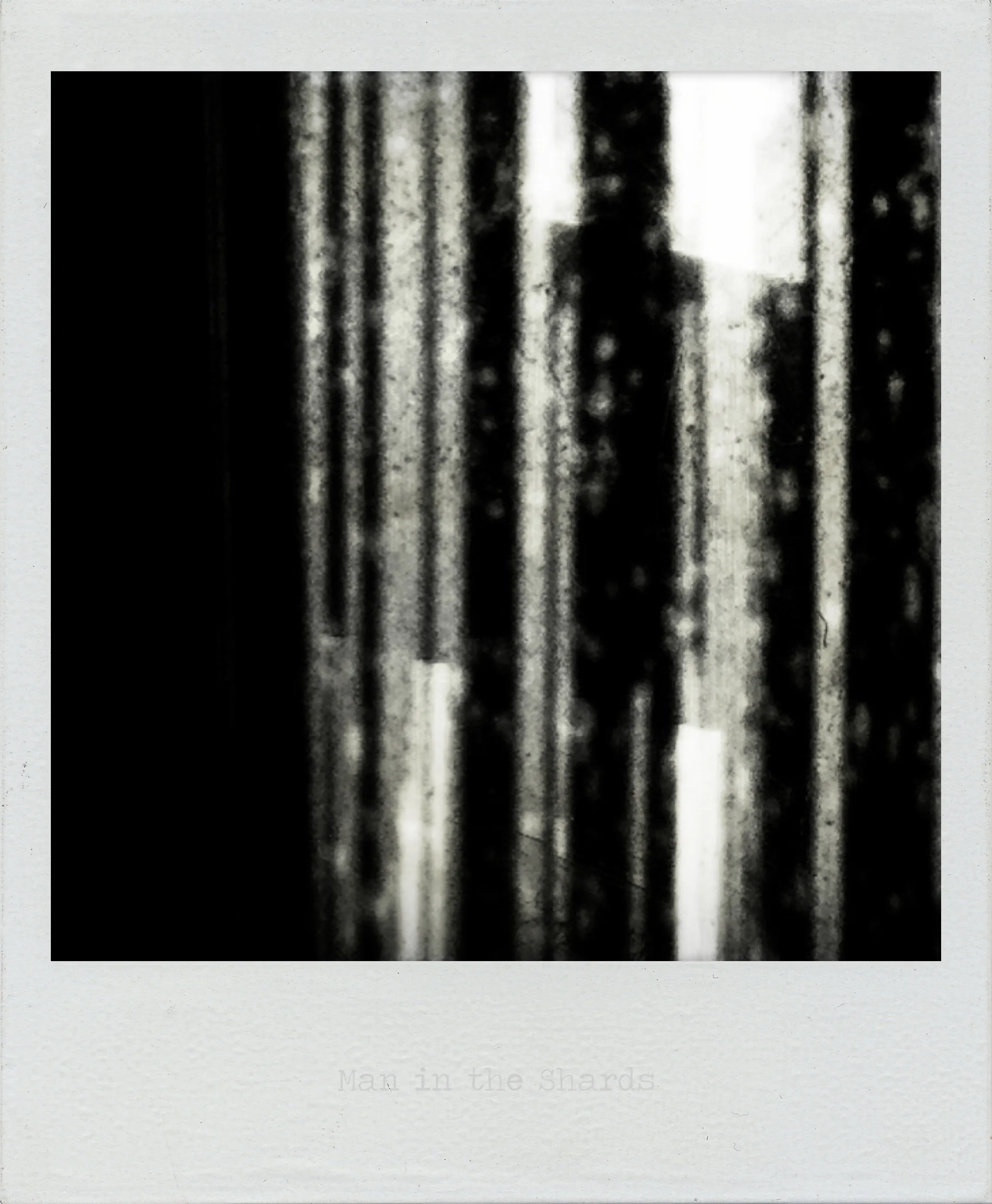

Vertical striations create a rhythm of revelation and concealment - light and dark bands alternating like broken slats or prison bars. After Satan occupied the hell, now Man occupies the shards.

The fragmentation is more regular here, almost architectural. The vertical channels suggest not organic decay but structural failure, something that once held together now broken into pieces. Man doesn’t exist whole within this space but is distributed across the fragments, visible only in pieces, through gaps, in the intervals between damage.

“Shards” implies violence - something shattered, broken apart with force. Man IN the shards could mean trapped within fragmentation, or it could mean Man IS the shards, his presence only legible through brokenness. There’s no whole figure to find here, only these vertical glimpses, these narrow channels where light penetrates the darkness.

The pattern suggests bars, containment, a cage made of shards themselves. Or perhaps it’s the opposite - the shards are what remain of barriers that have failed, and we’re seeing through them to where Man exists on the other side.

Following the series’ logic: from blight through various agents of decay to Satan in the hell, and now to Man in the shards. Humanity’s location is within fragmentation itself.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

Man in the Shards presents a fractured field of vertical lines, blurred transitions, and dark, indistinct zones. The composition is dense and disorienting—black-and-white striations dominate the frame, creating the illusion of glass, barcode, or broadcast interference. Among these layered textures, something begins to emerge—or perhaps disappear. A form. A presence. A possible figure embedded in or eclipsed by the noise.

The title insists on figuration: Man in the Shards. It proposes a subject—a man—situated not in a space, but in shards. Not just surrounded by fragmentation, but constituted through it. The word “shards” evokes breakage, trauma, and the aftermath of rupture. The implication is that what we see is not a whole, but a residue: of a body, a signal, a self.

This raises a fundamental question: how do we locate subjectivity within fractured systems of representation? The image resists clarity. There is no identifiable face, no distinct gesture. Instead, the possible figure is splintered across vertical planes, each one slightly offset, like a corrupted video stream or a shattered mirror. It is unclear whether the man is behind these surfaces or part of them.

Visually, the image borrows from a range of sources: surveillance aesthetics, glitch media, noir cinematography. But it is not derivative. Rather, it mobilizes these languages to interrogate how bodies—and particularly male-coded bodies—are constructed and constrained by systems of mediation. This is not a heroic or monumental masculinity, but one rendered ghostly, interrupted, distributed.

The formal qualities support this reading. The verticality of the lines imposes a rigid structure, as if the image were scanned, sorted, or imprisoned. Within this grid, detail dissolves. Light bleeds into dark. Edges blur. The “shards” are not clean cuts; they are smudged, unresolved fragments. This aesthetic imprecision mirrors the conceptual ambiguity: the man is both present and absent, coherent and undone.

The image resists narrative closure. Is this a portrait? A crime scene? A ghost transmission? It offers no resolution. This refusal is not a limitation, but a strategy. In withholding clarity, the work foregrounds the viewer’s impulse to impose meaning, to reconstruct a figure from shards. That act—of stitching together coherence from disruption—is precisely what the image scrutinizes.

There is also a sociopolitical undercurrent. In an era of fragmented identity, digital profiling, and algorithmic sorting, Man in the Shards visualizes the ways individuals are split across data points and representations. The body becomes a trace, a statistical blur. Visibility itself becomes suspect: to be seen is not to be known, but to be processed, indexed, abstracted.

Yet the image is not entirely cynical. There is something insistently human about the figure that haunts it. The very fact that we perceive a presence—however unstable—testifies to the resilience of subjectivity amid distortion. The shards do not eliminate the man; they reconfigure him. What emerges is not a disappearance, but a transformation: identity as assemblage, as flicker, as refusal to settle.

Ultimately, Man in the Shards offers no easy metaphors. It does not moralize about fragmentation, nor does it mourn a lost wholeness. Instead, it presents a condition: to exist within mediated space is to be partially visible, partially constructed, and constantly reframed. The man in the shards is not trapped. He is the artifact of a system—and possibly its critique.

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

Vertical striations create a rhythm of revelation and concealment - light and dark bands alternating like broken slats or prison bars. After Satan occupied the hell, now Man occupies the shards.

The fragmentation is more regular here, almost architectural. The vertical channels suggest not organic decay but structural failure, something that once held together now broken into pieces. Man doesn’t exist whole within this space but is distributed across the fragments, visible only in pieces, through gaps, in the intervals between damage.

“Shards” implies violence - something shattered, broken apart with force. Man IN the shards could mean trapped within fragmentation, or it could mean Man IS the shards, his presence only legible through brokenness. There’s no whole figure to find here, only these vertical glimpses, these narrow channels where light penetrates the darkness.

The pattern suggests bars, containment, a cage made of shards themselves. Or perhaps it’s the opposite - the shards are what remain of barriers that have failed, and we’re seeing through them to where Man exists on the other side.

Following the series’ logic: from blight through various agents of decay to Satan in the hell, and now to Man in the shards. Humanity’s location is within fragmentation itself.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

Man in the Shards presents a fractured field of vertical lines, blurred transitions, and dark, indistinct zones. The composition is dense and disorienting—black-and-white striations dominate the frame, creating the illusion of glass, barcode, or broadcast interference. Among these layered textures, something begins to emerge—or perhaps disappear. A form. A presence. A possible figure embedded in or eclipsed by the noise.

The title insists on figuration: Man in the Shards. It proposes a subject—a man—situated not in a space, but in shards. Not just surrounded by fragmentation, but constituted through it. The word “shards” evokes breakage, trauma, and the aftermath of rupture. The implication is that what we see is not a whole, but a residue: of a body, a signal, a self.

This raises a fundamental question: how do we locate subjectivity within fractured systems of representation? The image resists clarity. There is no identifiable face, no distinct gesture. Instead, the possible figure is splintered across vertical planes, each one slightly offset, like a corrupted video stream or a shattered mirror. It is unclear whether the man is behind these surfaces or part of them.

Visually, the image borrows from a range of sources: surveillance aesthetics, glitch media, noir cinematography. But it is not derivative. Rather, it mobilizes these languages to interrogate how bodies—and particularly male-coded bodies—are constructed and constrained by systems of mediation. This is not a heroic or monumental masculinity, but one rendered ghostly, interrupted, distributed.

The formal qualities support this reading. The verticality of the lines imposes a rigid structure, as if the image were scanned, sorted, or imprisoned. Within this grid, detail dissolves. Light bleeds into dark. Edges blur. The “shards” are not clean cuts; they are smudged, unresolved fragments. This aesthetic imprecision mirrors the conceptual ambiguity: the man is both present and absent, coherent and undone.

The image resists narrative closure. Is this a portrait? A crime scene? A ghost transmission? It offers no resolution. This refusal is not a limitation, but a strategy. In withholding clarity, the work foregrounds the viewer’s impulse to impose meaning, to reconstruct a figure from shards. That act—of stitching together coherence from disruption—is precisely what the image scrutinizes.

There is also a sociopolitical undercurrent. In an era of fragmented identity, digital profiling, and algorithmic sorting, Man in the Shards visualizes the ways individuals are split across data points and representations. The body becomes a trace, a statistical blur. Visibility itself becomes suspect: to be seen is not to be known, but to be processed, indexed, abstracted.

Yet the image is not entirely cynical. There is something insistently human about the figure that haunts it. The very fact that we perceive a presence—however unstable—testifies to the resilience of subjectivity amid distortion. The shards do not eliminate the man; they reconfigure him. What emerges is not a disappearance, but a transformation: identity as assemblage, as flicker, as refusal to settle.

Ultimately, Man in the Shards offers no easy metaphors. It does not moralize about fragmentation, nor does it mourn a lost wholeness. Instead, it presents a condition: to exist within mediated space is to be partially visible, partially constructed, and constantly reframed. The man in the shards is not trapped. He is the artifact of a system—and possibly its critique.