Some Savior

Some Savior

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

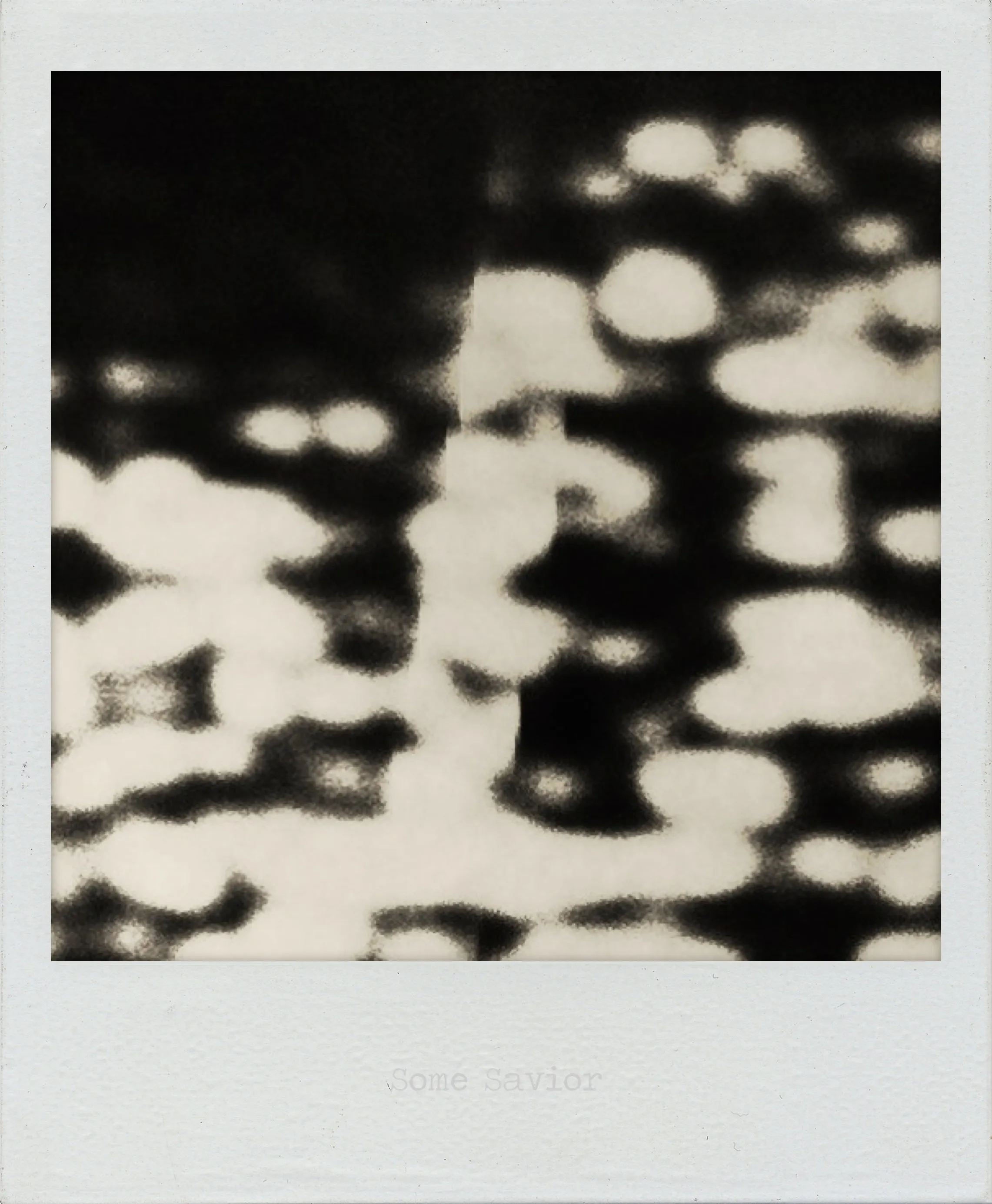

Light and dark interpenetrate in complex, organic patterns - neither clearly winning, neither offering resolution. The shapes interlock like puzzle pieces that no longer fit properly, or like a map of territories in constant flux. After Satan in the hell and Man in the shards, the series gives us a savior - but hedges immediately with “some.”

That qualifier is everything. Not THE savior, not even A savior, but “some savior” - as if to say: this is what passes for salvation in a world governed by decay. The tone is ambivalent at best, sarcastic at worst. This savior doesn’t restore order or wholeness; it exists within the same system of fragmentation and compromise we’ve been witnessing throughout.

The patterns suggest biological processes viewed under magnification - cells, membranes, the microscopic architecture of breakdown. Or light finding its way through extensive damage, creating these irregular shapes where visibility is possible.

The savior might be simply that light persists at all, that darkness hasn’t achieved totality, even if what remains is this chaotic interpenetration rather than any clear triumph.

Following the series’ progression through various personifications of decay and endurance, “some savior” feels like the exhausted acknowledgment that salvation, if it exists here, is compromised, fragmented, no more whole than anything else. It saves nothing - it just… persists, somehow.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

Some Savior is built from ambiguity. The image consists of cloud-like white shapes floating on a dark ground, their edges softly diffused, their distribution uneven. A subtle vertical seam divides the composition, implying symmetry but denying exact mirroring. Among the scattered forms, the eye might detect a figure—or at least the shape of one. But like a vision in smoke or static, it never fully resolves.

The title is telling. “Some Savior” is both vague and loaded. The indefinite article “some” drains the term “savior” of grandeur, authority, or specificity. It implies a fallback, a placeholder, a provisional redeemer. It may be sarcastic, resigned, or merely uncertain. This ambivalence animates the entire composition. We are not shown a savior, only a pattern into which one might be projected.

The image leans heavily into pareidolia—the tendency of the human mind to find faces, figures, or meaning in randomness. There’s no actual depiction here, but that doesn’t stop the eye from seeking it. The dark patches become voids, the lighter ones suggest mass or presence. At the center, a vertical path or column evokes a spine, a body, a torch. Nothing is explicit, but everything is implicated.

This visual instability mirrors a cultural one. In a moment saturated by iconography—religious, political, commercial—the image asks: what happens when we no longer believe in what the symbols once meant, but still feel their pull? Some Savior does not offer reassurance. It offers the framework of belief, hollowed out and left to float in an abstract field. The savior, if present, is only ever partial, flickering, assembled in the viewer’s perception rather than the artist’s design.

From a formal standpoint, the composition is minimal yet active. The shapes are not static but feel in flux, like a disrupted signal or a field of interference. The soft edges deny resolution. This blur functions metaphorically: clarity is unavailable, certainty is out of reach. The grid of presence and absence suggests both noise and structure, pattern and collapse.

There’s also an implied critique in the title’s casual tone. “Some Savior” may mock the grand narratives that promise rescue, transcendence, or order. Or it may register fatigue with the persistent cultural demand for resolution. Either way, the phrase undermines messianic logic. The image participates in that undermining—not through destruction, but through diffusion.

Importantly, the work doesn’t resolve into nihilism. It remains open, uncertain, ambivalent. The desire for salvation is neither fulfilled nor mocked—it’s acknowledged as a recurring perceptual reflex. The central “figure” becomes a mirror, reflecting the viewer’s own search for structure and meaning.

Ultimately, Some Savior functions less as an image of a figure and more as a field of potential. It stages an encounter with the edge of representation—where belief falters, where form recedes, and where the idea of salvation becomes just another ghost in the visual noise. The work does not say there is no savior. It simply says: this is what it looks like when you have to imagine one yourself.

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

Light and dark interpenetrate in complex, organic patterns - neither clearly winning, neither offering resolution. The shapes interlock like puzzle pieces that no longer fit properly, or like a map of territories in constant flux. After Satan in the hell and Man in the shards, the series gives us a savior - but hedges immediately with “some.”

That qualifier is everything. Not THE savior, not even A savior, but “some savior” - as if to say: this is what passes for salvation in a world governed by decay. The tone is ambivalent at best, sarcastic at worst. This savior doesn’t restore order or wholeness; it exists within the same system of fragmentation and compromise we’ve been witnessing throughout.

The patterns suggest biological processes viewed under magnification - cells, membranes, the microscopic architecture of breakdown. Or light finding its way through extensive damage, creating these irregular shapes where visibility is possible.

The savior might be simply that light persists at all, that darkness hasn’t achieved totality, even if what remains is this chaotic interpenetration rather than any clear triumph.

Following the series’ progression through various personifications of decay and endurance, “some savior” feels like the exhausted acknowledgment that salvation, if it exists here, is compromised, fragmented, no more whole than anything else. It saves nothing - it just… persists, somehow.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

Some Savior is built from ambiguity. The image consists of cloud-like white shapes floating on a dark ground, their edges softly diffused, their distribution uneven. A subtle vertical seam divides the composition, implying symmetry but denying exact mirroring. Among the scattered forms, the eye might detect a figure—or at least the shape of one. But like a vision in smoke or static, it never fully resolves.

The title is telling. “Some Savior” is both vague and loaded. The indefinite article “some” drains the term “savior” of grandeur, authority, or specificity. It implies a fallback, a placeholder, a provisional redeemer. It may be sarcastic, resigned, or merely uncertain. This ambivalence animates the entire composition. We are not shown a savior, only a pattern into which one might be projected.

The image leans heavily into pareidolia—the tendency of the human mind to find faces, figures, or meaning in randomness. There’s no actual depiction here, but that doesn’t stop the eye from seeking it. The dark patches become voids, the lighter ones suggest mass or presence. At the center, a vertical path or column evokes a spine, a body, a torch. Nothing is explicit, but everything is implicated.

This visual instability mirrors a cultural one. In a moment saturated by iconography—religious, political, commercial—the image asks: what happens when we no longer believe in what the symbols once meant, but still feel their pull? Some Savior does not offer reassurance. It offers the framework of belief, hollowed out and left to float in an abstract field. The savior, if present, is only ever partial, flickering, assembled in the viewer’s perception rather than the artist’s design.

From a formal standpoint, the composition is minimal yet active. The shapes are not static but feel in flux, like a disrupted signal or a field of interference. The soft edges deny resolution. This blur functions metaphorically: clarity is unavailable, certainty is out of reach. The grid of presence and absence suggests both noise and structure, pattern and collapse.

There’s also an implied critique in the title’s casual tone. “Some Savior” may mock the grand narratives that promise rescue, transcendence, or order. Or it may register fatigue with the persistent cultural demand for resolution. Either way, the phrase undermines messianic logic. The image participates in that undermining—not through destruction, but through diffusion.

Importantly, the work doesn’t resolve into nihilism. It remains open, uncertain, ambivalent. The desire for salvation is neither fulfilled nor mocked—it’s acknowledged as a recurring perceptual reflex. The central “figure” becomes a mirror, reflecting the viewer’s own search for structure and meaning.

Ultimately, Some Savior functions less as an image of a figure and more as a field of potential. It stages an encounter with the edge of representation—where belief falters, where form recedes, and where the idea of salvation becomes just another ghost in the visual noise. The work does not say there is no savior. It simply says: this is what it looks like when you have to imagine one yourself.