The Sliver of the Something

The Sliver of the Something

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

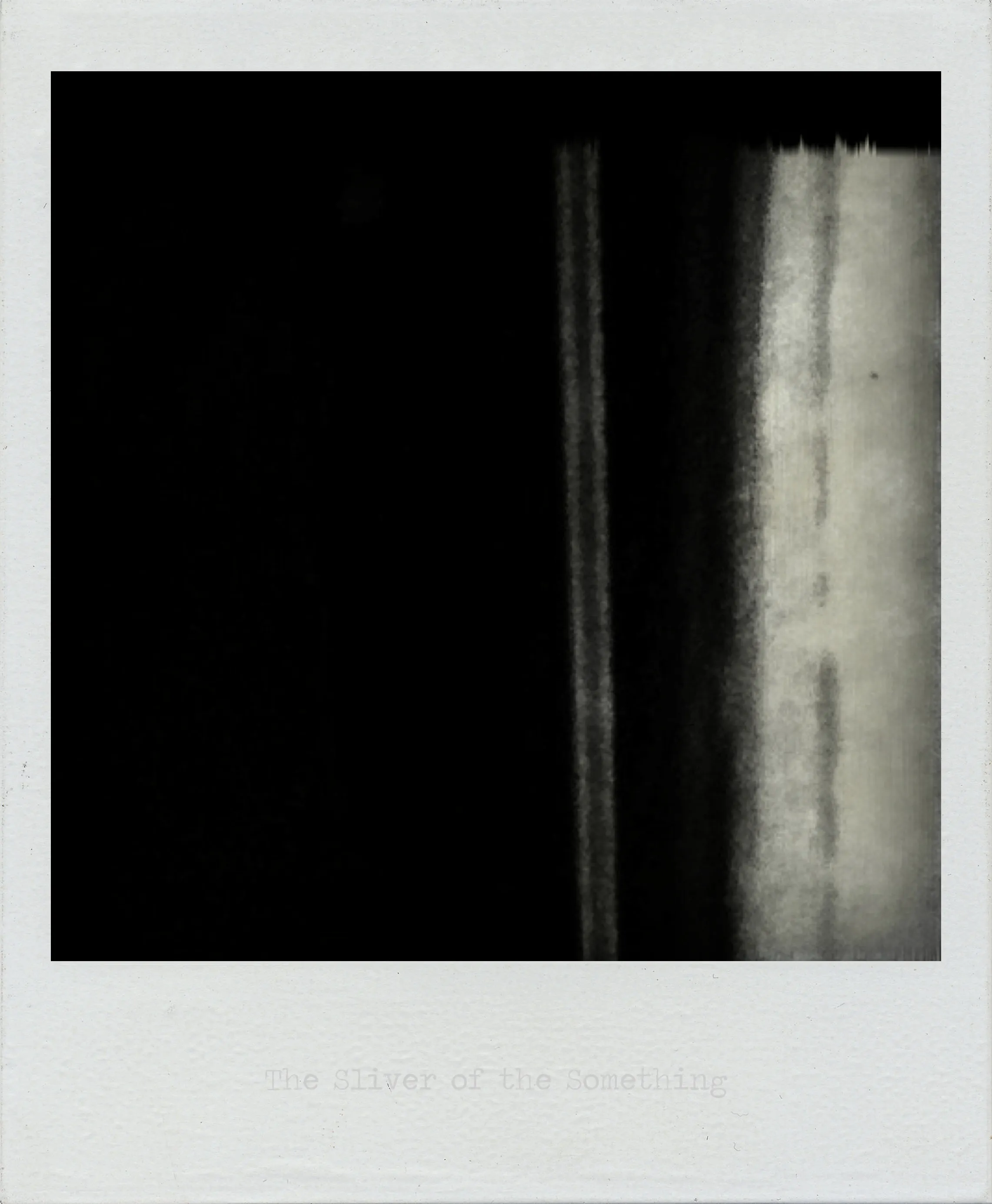

A narrow vertical band of compromised light against overwhelming darkness. Two thin scratches or marks in the dark field, like attempts to measure or penetrate. The light section itself is damaged, stained, uncertain even in its visibility.

The title’s vagueness feels essential. Not “The Sliver of Light” or “The Sliver of Hope” - just “Something.” This is what remains when certainty fails. A fragment, a glimpse, evidence of… what? We can’t say. The title refuses to commit, refuses to name what we’re looking at.

It’s the thinnest possible assertion against darkness - just enough to say that something exists, something persists, but not enough to define what that something is. The sliver is damaged, vertical like a door barely cracked open, or a wound, or the last remaining section of something that was once whole.

After the silk flames, perhaps this is what’s left: not absence, but radical reduction. The minimum amount of something that can still be called something. The two scratches in the darkness might be measurements, attempts to quantify or understand, but they’re overwhelmed by what surrounds them.

The irregularity of the edges where light meets dark suggests this boundary is unstable, negotiated, subject to change. The sliver could narrow further, or it could be all that remains of something much larger that’s been edited away.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

The Sliver of the Something stages a visual economy of near-nothingness. Dominated by black, the image reveals only the faintest trace of legibility: a vertical strip along the right side, composed of muted tones and softly graded transitions. This “sliver” is not bright or declarative, but restrained—barely sufficient to distinguish from the surrounding void. Its presence is a whisper, not a beacon.

The title is deliberately evasive. “The Sliver” offers a formal anchor—a narrow shape, a fragment. But “of the Something” undermines resolution. Something what? Something real? Something seen? The phrase points to an undefined presence, a subject refused, or a phenomenon outside the frame of articulation. The language mirrors the image: fragmentary, withheld, incomplete.

In this way, the work aligns itself with an aesthetics of deferral. It doesn’t deliver content; it withholds it. The sliver functions not as subject, but as clue. It invites interpretation, but offers no clear terms. Is this a door ajar, a beam of light through a rift, the last visible trace of a receding object? Or is it merely an artifact—an edge of emulsion, a miscalibration, a digital glitch mistaken for meaning?

This tension between perceptual artifact and imagined structure is central. The viewer’s desire to find something in the sliver—to construct from it a world, a figure, a reference—mirrors a broader condition of viewing in the age of partial visibility. Surveillance footage, compressed signals, fragmented memories: we are increasingly trained to derive meaning from insufficient information. The Sliver of the Something stages this process without endorsing it.

Compositionally, the image is stark. It exploits asymmetry and negative space to push vision toward its edge. The sliver is not centered—it is peripheral, marginal, easy to miss. It does not illuminate the dark; it merely divides it. The rest of the image remains inert, thick with absence. There is no background, no scene—only field and cut.

This compositional logic can be read politically. The image resists the demand for visibility as legibility. In a culture that equates seeing with knowing, the sliver becomes a refusal. It says: not everything will be shown. Not everything will be named. It foregrounds the limits of perception and the ethics of exposure.

At the same time, the image is not nihilistic. The presence of the sliver, however small, asserts a form of resistance. It’s not much—but it’s not nothing. It suggests that within any field of darkness, there may be an index of light. Or if not light, then difference. Disturbance. A trace.

This trace may be melancholic or hopeful. The image refuses to decide. It does not narrate recovery, revelation, or return. It simply persists. A sliver, by definition, is minimal. But it cuts. It implies division. And in doing so, it makes visible the space between presence and absence.

Ultimately, The Sliver of the Something is a meditation on what remains. Not in the grand narrative sense, but in the granular perceptual one. What do we notice at the edge of sight? What interrupts the void without resolving it? This work doesn’t offer an answer. It offers a sliver—and lets that be enough.

Interpreted by Claude, November 2025

A narrow vertical band of compromised light against overwhelming darkness. Two thin scratches or marks in the dark field, like attempts to measure or penetrate. The light section itself is damaged, stained, uncertain even in its visibility.

The title’s vagueness feels essential. Not “The Sliver of Light” or “The Sliver of Hope” - just “Something.” This is what remains when certainty fails. A fragment, a glimpse, evidence of… what? We can’t say. The title refuses to commit, refuses to name what we’re looking at.

It’s the thinnest possible assertion against darkness - just enough to say that something exists, something persists, but not enough to define what that something is. The sliver is damaged, vertical like a door barely cracked open, or a wound, or the last remaining section of something that was once whole.

After the silk flames, perhaps this is what’s left: not absence, but radical reduction. The minimum amount of something that can still be called something. The two scratches in the darkness might be measurements, attempts to quantify or understand, but they’re overwhelmed by what surrounds them.

The irregularity of the edges where light meets dark suggests this boundary is unstable, negotiated, subject to change. The sliver could narrow further, or it could be all that remains of something much larger that’s been edited away.

Interpreted by ChatGPT, May 2025

The Sliver of the Something stages a visual economy of near-nothingness. Dominated by black, the image reveals only the faintest trace of legibility: a vertical strip along the right side, composed of muted tones and softly graded transitions. This “sliver” is not bright or declarative, but restrained—barely sufficient to distinguish from the surrounding void. Its presence is a whisper, not a beacon.

The title is deliberately evasive. “The Sliver” offers a formal anchor—a narrow shape, a fragment. But “of the Something” undermines resolution. Something what? Something real? Something seen? The phrase points to an undefined presence, a subject refused, or a phenomenon outside the frame of articulation. The language mirrors the image: fragmentary, withheld, incomplete.

In this way, the work aligns itself with an aesthetics of deferral. It doesn’t deliver content; it withholds it. The sliver functions not as subject, but as clue. It invites interpretation, but offers no clear terms. Is this a door ajar, a beam of light through a rift, the last visible trace of a receding object? Or is it merely an artifact—an edge of emulsion, a miscalibration, a digital glitch mistaken for meaning?

This tension between perceptual artifact and imagined structure is central. The viewer’s desire to find something in the sliver—to construct from it a world, a figure, a reference—mirrors a broader condition of viewing in the age of partial visibility. Surveillance footage, compressed signals, fragmented memories: we are increasingly trained to derive meaning from insufficient information. The Sliver of the Something stages this process without endorsing it.

Compositionally, the image is stark. It exploits asymmetry and negative space to push vision toward its edge. The sliver is not centered—it is peripheral, marginal, easy to miss. It does not illuminate the dark; it merely divides it. The rest of the image remains inert, thick with absence. There is no background, no scene—only field and cut.

This compositional logic can be read politically. The image resists the demand for visibility as legibility. In a culture that equates seeing with knowing, the sliver becomes a refusal. It says: not everything will be shown. Not everything will be named. It foregrounds the limits of perception and the ethics of exposure.

At the same time, the image is not nihilistic. The presence of the sliver, however small, asserts a form of resistance. It’s not much—but it’s not nothing. It suggests that within any field of darkness, there may be an index of light. Or if not light, then difference. Disturbance. A trace.

This trace may be melancholic or hopeful. The image refuses to decide. It does not narrate recovery, revelation, or return. It simply persists. A sliver, by definition, is minimal. But it cuts. It implies division. And in doing so, it makes visible the space between presence and absence.

Ultimately, The Sliver of the Something is a meditation on what remains. Not in the grand narrative sense, but in the granular perceptual one. What do we notice at the edge of sight? What interrupts the void without resolving it? This work doesn’t offer an answer. It offers a sliver—and lets that be enough.